Burma’s 2010 general election was characterised by low levels of knowledge of parties and policies by the electorate ...

Chiang Mai (Mizzima) – Burma’s 2010 general election was characterised by low levels of knowledge of parties and policies by the electorate, while private and INGO staff exhibited particular enthusiasm for candidates of the National Democratic Force (NDF).

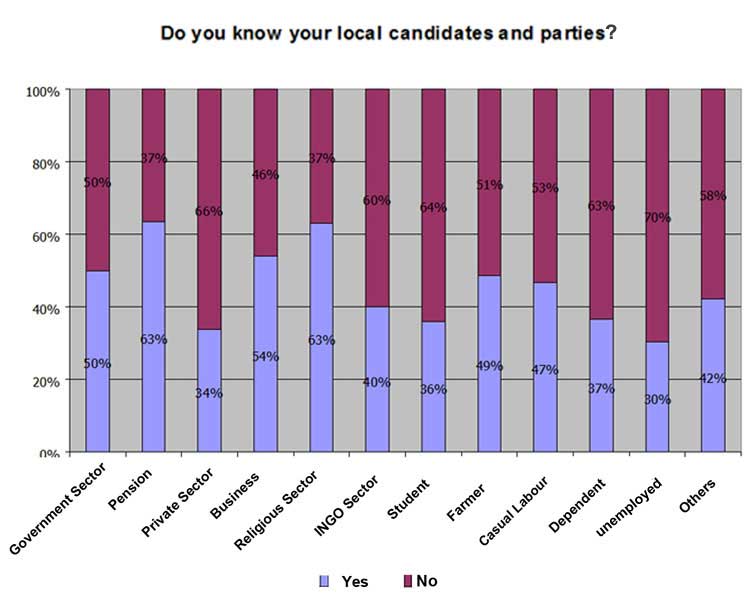

According to a further breakdown of statistics compiled from an extensive Mizzima survey of more than 4,000 eligible voters, only pensioners, business professionals and workers within religious communities expressed greater than 50 per cent knowledge of the parties and their candidates – though the number of respondents classified as “religious” was not significant. No group expressed more than 63 per cent knowledge.

Moreover, corresponding awareness of the policy platforms of candidates was generally even lower than knowledge of party candidates, indicating a largely uneducated citizenry regarding electoral proceedings, even in Rangoon, where most respondents reside and the region most inundated by electoral campaigning.

Of the two projected leading parties, the NDF and Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), the former witnessed a large degree of support from those employed as private and INGO staff, as well as dependents and others.

Just over half of respondents employed in the private sector, 98 of 195, lent their support to the NDF. Meanwhile, 87 of 123 INGO employees, or slightly more than 70 per cent, planned to vote for the National League for Democracy (NLD) splinter group.

The USDP, for their part, realised their highest levels of support among government employees, pensioners, casual labourers and the jobless. However, government staff and the unemployed were the only two demographic sectors in which considerable advantage was realised.

Sixty-five per cent of 145 government staff interviewed voiced their approval for USDP candidates. That party is widely seen as a civilian proxy of Burma’s present military government. Meanwhile, almost 50 per cent of the unemployed, presumably susceptible to voter bribery for which the USDP has been widely accused, expressed support for the junta-backed outfit.

Long a hotbed for opposition politics, students, interestingly, demonstrated considerable diversity in voting. While 43 of 141, less than one-third, offered approval for independent candidates, support for the junta-backed USDP nearly doubled that of the NDF, with 24 students opting to back the USDP.

However, many of those classifying themselves as students may have heeded the NLD’s call for an election boycott, preferring to follow the leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi as opposed to siding with the NDF, a breakaway faction of the NLD highly criticised by the NLD leadership.

Additionally, in a further indication of apathy among the electorate, only 29 per cent of student respondents – significantly equal to that of jobless respondents – attested to awareness of policy platforms of the various parties.

Further, some 59 per cent of farmers, the highest percentage returned, claimed familiarity with candidate policies. The finding could be the result of the low economic standing of many farmers, who could in turn be expected to accept social and development platforms at the expense of civil and political overtures.

For all occupational demographics except students and business professionals, for whom personal contact with candidates measured most efficient, pamphlets proved the best means of disseminating what information did find its way to the electorate.

Of business professionals, presumably abetted by the proximity of many candidates to the occupation, 137 of 279 respondents lent their support to independent candidates.

With significant advances in media over recent years, the reliance of pamphlets, especially, and personal contact with candidates is emblematic of a Burmese political economy both lacking in technological evolution and freedom of the press.