When the three Karen activists Naw Ohn Hla, Saw Elbert Cho and Sa Thein Zaw Min were released, due to the fact that they have already served 22 days, which were already more then sentenced 15 days of imprisonment punishment for breaching the government’s prohibition order of not to use the term “martyrs’ day” to commemorate the death of Saw Bo U Gyi, the message is clear that the Yangon Regional government will not budge from its political stance regarding the issue.

The usage of the term “martyr” is banned by the authorities, perhaps reasoning that only those assassinated on July 19, 1947 were entitled to be addressed as such.

The commemoration of martyrs’ day is yearly held for General Aung San and seven other leaders of the pre-independence interim government, and one bodyguard – Thakin Mya, Ba Cho, Abdul Razak, Ba Win, Mahn Ba Khaing, Sao San Tun, Ohn Maung and Ko Htwe – all of whom were assassinated on that day in 1947.

Karen revolutionary leader Saw Ba U Gyi, who was murdered on August 12, 1950 is also commemorated annually by the Karen people as Karen Martyrs’ Day.

This year on August 12, more than 100 people, led by Naw Ohn Hla, So Elbert Cho and Sa Thein Zaw Min, participated in an event to mark the 69th anniversary of Karen Martyrs’ Day in front of City Hall in Kyauktada Township, Yangon, which led them to be charged with Article 20, unlawful assembly act.

As if to drive home the message on what it has done is politically and legally correct, the police captain of Kyauktada Township opened unlawful assembly cases against Daw Sein Htwe and Ma Zarchi Linn of the Democracy, Peace and Women (DPW) group, and Naw Larshee Htoo of the Karen Women’s Union (KWU) for leading a rally of some 130 people in solidarity with three Karen activists at the court, who were found guilty on October 2 for holding an earlier unlawful gathering on Karen Martyrs’ Day in Yangon.

Burma’s major ethnic groups; map from US Campaign for Burma.

Remarkably, while Larshee Htoo is Karen, Daw Sein Htwe and Ma Zarchi Linn are ethnic Bamar or Burmese. They are now being sued and were asked to appear before the Kyauktada Police Station. The rally included Karen, Karenni, Pa-O, Bamar and other ethnic groups, which resembled a broad civilian coalition against the heavy-handedness of the government.

Reportedly, DPW and KWU issued a joint statement condemning the allegations, saying that they will continue to protest against the lawsuits. Moreover, Ko Min Nay Htoo general secretary of the DPW said that if police arrest these three activists, all the supporters who came to the court on September 27 will go to the police station and turn themselves in to be arrested, according to recent report of The Irrawaddy.

Linkage of Bamar supremacy doctrine and assimilation

It is a well established fact that the Bamar political elite and the military or Burma army top brass accepted the concept that the present day Burma or Myanmar stems from immemorial Burmese empires of Anawratha, Kyansitthar and Alaungpaya. In other words, the territories and inhabitants of different ethnicity are all also subjects of the Burmese empire, which the British colonized it in the 18th century and the governing power falls back into the hands of Bamar political leadership as Burma regained its freedom back again in 1948.

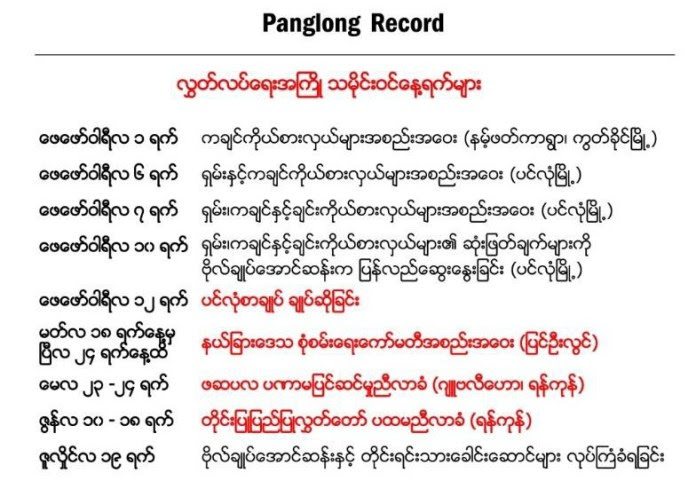

The ethnic states and their people, in contrast, see the emergence of the new political entity “Union of Burma” through the virtue of Panglong Agreement signed in 1947, between the Burma Proper also known as Ministerial Burma under the British, with the Chin, Shan and the Kachin people representatives, to form the Union of Burma that eventually took place in January 1948.

Thus, the difference of concept regarding the emergence of the new political entity prevailed from the outset, which becomes distinctively profound as the successive Bamar-dominated governments strive for unitary system, with the Bamar ethnic monopolizing the country’s political powers that lasted to these days. The ethnic nationalities felt betrayed as the essence of the Panglong Agreement is to establish a federal union based on territory and ethnicity. And it has been the cause of ethnic conflict which is still raging on until today.

This incompatible emergence of the country concept is reinforced by what we call “Burmanization” or forced, institutionalized assimilation scheme of the Bamar-dominated successive governments, meted out upon the non-Bamar ethnic nationalities.

The ethnic nationalities have repeatedly complained about the ongoing institutionalized assimilation scheme, while almost all ethnicity have taken up arms to strive for their rights of self-determination, which is intertwined with preserving their cultural and identity heritage.

Bamar awakening

The good thing or the blessing in disguise about it is that the new generation of Bamar activists and the journalists have now taken up position to address this ethnic nationalities grievances openly, which until lately has been never been the case and also a tabu theme.

For example, well known journalist Sithu Aung Myint, Thet Swe Win of Synergy Center for Social Harmony and Myanmar Cultural Research Organization director Ye Haing Aung and Ko Aung Aung have voiced their concern and make public the negative impact of such undertakings by the Bamar authorities, in a recent weekly discussion forum in the Voice of America regarding the assimilation issue.

All pointed out that apart from the narrow-mindedness of the authorities in prohibiting the usage of “martyrs’ day” term for the Karen, the forcible erection of the late General Aung San’s statue, who was the father of State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi, in Kachin, Chin, Kayah (Karenni) States; the naming of the bridge after the late General Aung San against the wish of the Mon population; are examples seen as forced assimilation actions carried out by the National League for Democracy (NLD) government.

Thet Swe Win went so far as to accuse the government of employing Burmanization as a policy when the above mentioned controversial issues are taken into account and improper handling of the sensitive issues by the government.

Correcting past mistakes and census irregularities

Similar assimilation acts, whether intentionally or unintentional, also pointed out the government’s implementation urge, even if it is an unwritten policy.

For example, on September 23 during the Mon State parliamentary session, Thathon (1) representative Daw Khein Le Le tabled a question regarding ethnic rights. She asked whether proper title names in identity cards, passports and family registrations that should correspond with the ethnic way of addressing will be considered and corrected accordingly.

The Mon immigration and population minister replied that all individual wishes to be included as titles will be allowed. However, he said in order to correct the past mistakes the cases concerned will have to seek approval from union (central) level authorities.

The question behind this is the problem of addressing the ethnic title names of “Saw, Sai, Min, Naw, Nang, Mi” and so on with replacement of “U, Daw, Maung, Ma” which are Bamar way of addressing titles and Burmanized form for many years.

Some headmasters and Ministry of Labor, Immigration and Population authorities even go so far as to change the ethnic names into Bamar to make it easy for them to address. And to correct such mistakes in the identity papers and passports, the cases will have to go all the way to union level minister means, the government isn’t ready to correct the past mistakes or failures made during registration.

On top of this, the Ministry of Labor, Immigration and Population after five years of population census it still cannot officially announced the result, due to the irregularities in the 135 ethnic group counts, which were overlapping and at times repeated even though they belong to the same category.

For example, ethnic group “Kachin” can also be filled in as “Jinghpaw,” wrote the Voice of America in its Burmese section recent report.

The same flaw of repeating the same group with a different name examples are “Shan Gyi” and “Tai-Lon,” are different names of the same ethnic group. “Shan Gale” and “Tai-Lay” are also the same.

Outlook

Given such ingrained concepts regarding the emergence of the political entity called Burma or Myanmar in 1948, the commitment to assimilate the non-Bamar ethnic groups into Bamar or “Myanmar” common identity by the Bamar-dominated successive governments, the nation-building process is deeply flawed, even from the theoretical point of view.

Firstly, it is true that a common official language, lingua franca, is needed and no one actually argued so far regarding this issue and even endorsed, directly or indirectly, that Myanmar or Bamar as an accepted common language for the country.

But this doesn’t mean that the diverse ethnic nationalities and minorities will have to be culturally and linguistically completely assimilated into Bamar identity at the expense of losing their cultural and identity heritage.

If the country is to be accepted as a multi-ethnic state, a degree of acknowledgment and accommodation of the ethnic local languages should be allowed to exist along side the Bamar language in their respected area as dual official languages also. For a start, the seven major languages of Kachin, Shan, Karenni, Karen, Mon, Arakan and Chin should be granted official language status to be used in their respective states, such as in governmental agencies and the court, along side the Bamar language.

Secondly and most importantly, the Bamar political elite and military should reverse their thinking of being a colonial master, inherited back from the British, vis-à-vis the ethnic states, and should be completely altered. They should instead accept the reality that the present day country is a creation of voluntary participation of the ethnic nationalities through Panglong Agreement of 1947, which is the only legal bond between the Bamar and the ethnic nationalities.

If the two said issues or concepts could be agreed upon, comprehensive political settlement could be achievable within the mold of multi-ethnic state with federal system. If not, all interactions, including the year-long ongoing peace negotiations, will only evolve around win-lose or zero-sum game plan, resulting in never-ending conflict, which has lasted for nearly six decades since the military coup in 1962.